Try Building a Game

I do not make games for a living. I spend my time at work constructing data pipelines and building web APIs. One could reasonably ask why I would bother making a simple game that, most likely, only I will ever play. The answer is that building games is hard, even a simple game like Pong or Breakout. There is quite a bit to manage and it makes for a fun distraction for an afternoon while the toddler sleeps.

How does this translate beyond me? I honestly think there is something to the idea that games are a pinnacle of software design and implementation. They require graphics, sound, math, and user input at the very least. Many simple games include basic AI and other more advanced computer science topics one may never touch on in their day job. It provides a proven way to step outside your comfort zone and challenge yourself.

So, what did I build and how did I build it? I built Pong. I honestly didn’t intend to, at first. I was following an excellent tutorial on LÖVE and placed a white rectangle on a black screen. Once I made it move, I turned to myself and thought, I bet I can make Pong with what I know. Sure enough, I abandoned the tutorial and an hour later had a working Pong game with a dumb AI that was too good to be reasonably beaten.

This is where I started experimenting with physics, trying and eventually failing to have the ball match the player paddle’s acceleration. Still, despite being unable to make the more advanced game work without weird ball-paddle interactions, I feel like I found sparks of fun in trying to spike the ball such that AI paddle couldn’t keep up.

As previously stated, I built my pong using the LÖVE engine in fennel, a Lisp that compiles down to LÖVE’s scripting language of choice, Lua. I am currently on a Lisp kick, so fennel was the perfect way to get some more face time with a different dialect of Lisp than I used for my previous project, Common Lisp. I have long admired LÖVE for its simplicity as well as its easy to use nature, so it make for a natural choice for a game engine to start with. I could have chosen an engine in a language I was more familiar with, but where is the fun in that?

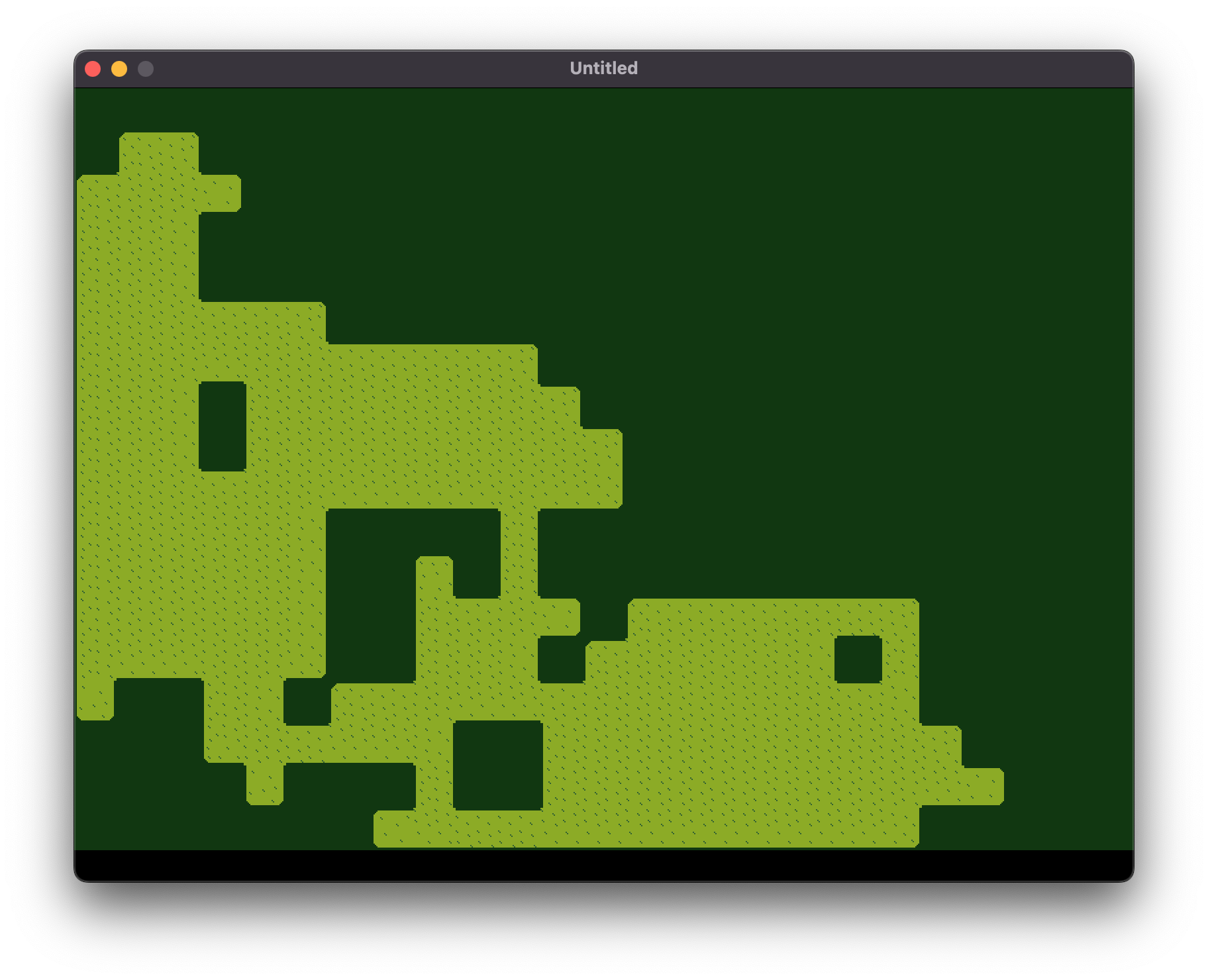

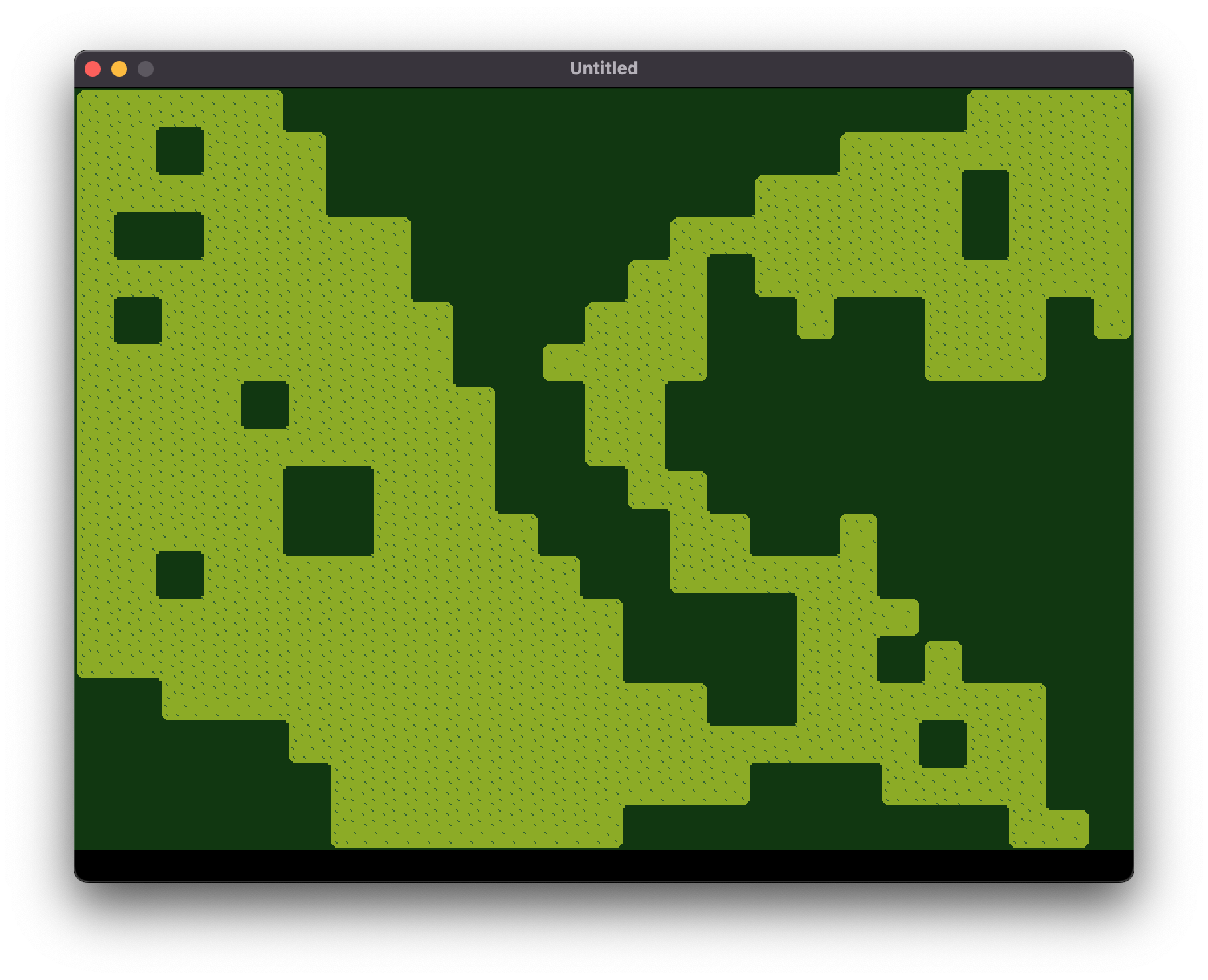

Pong is nice, but what about something meatier? After finishing Pong, I struggled to think of a good next project. Eventually I settled on a mining mini-game as mining was always one of my favorite parts of farming games such as Harvest Moon and Stardew Valley. I am only part way through the project so far, but I’ve made some good progress. I decided I wanted to randomly generate the layout and loot drops for each level of the mine. So far, I have been able to generate the layout of the mine level with nice auto-tiling to make the level look well put together.

It started this article, which gave the basics of generating a procedurally generated dungeon. The most important piece from that article was the fact that it utilized a random walk algorithm to achieve the random state without disconnected pieces of the level. Without diving into the code in the article, I just took the basic concepts and was able to implement it in fennel for LÖVE. I started with printing out the nested tables (Lua’s basic data structure stand-in for array and dictionaries) and representing the dungeon area with 1’s and 0’s. This gave me enough of an idea about shape before adding any proper rendering. I have the basic random walk code below. Please note, fennel does not support breaking out of a loop, therefore the bizarre handling of out-of-bounds indices.

(local dirs {:up [-1 0] :down [1 0] :left [0 -1] :right [0 1]})

(fn init-map []

(let [tile-map []]

(for [j 1 tile-height]

(let [row []]

(for [i 1 tile-width]

(table.insert row 1))

(table.insert tile-map row)))

tile-map))

(fn random-dir []

(local keyset [])

(each [key (pairs dirs)]

(table.insert keyset key))

(let [choice-index (love.math.random (length keyset))

choice-key (. keyset choice-index)

choice (. dirs choice-key)]

(unpack choice)))

(fn gen-map [max-tunnels max-length]

(let [num-tiles (* tile-width tile-height)

start (love.math.random num-tiles)

tile-map (init-map)]

(var curr-j (math.floor (/ start tile-height)))

(var curr-i (math.floor (math.fmod start tile-height)))

(for [tunnel 1 max-tunnels]

(let [(dj di) (random-dir)]

(for [tunnel-idx 1 max-length]

(when (< curr-j 1)

(set curr-j 1))

(when (> curr-j tile-height)

(set curr-j tile-height))

(when (< curr-i 1)

(set curr-i 1))

(when (> curr-i tile-width)

(set curr-i tile-width))

(tset tile-map curr-j curr-i 0)

(set curr-j (+ curr-j dj))

(set curr-i (+ curr-i di)))))

tile-map))

Next was tiling the level. For this, I used a simple but clever auto-tiling method where I labeled all my tiles by which sides were closed, using “l” and “r” for left and right and “t” and “b” for top and bottom. I kept the naming consistent and in the same order. I then walked around the map, looking for which sides were closed off and generating the appropriate matching key. For example, if the left and top sides were closed off, the matching key would be “lt.” I feel it is easier to look at code than explain an algorithm in plain English, so the relevant code is included below:

(local bg-tiles {:lt 1 :t 2 :rt 3 :l 7 :f 8 :r 9 :lb 13 :b 14 :rb 15 :lr 20 :tb 22 :lrt 28 :lrb 29 :ltb 30 :rtb 31 :lrtb 32})

(fn auto-tile [tile-map]

(local new-map (init-map))

(for [j 1 (length tile-map)]

(for [i 1 (length (. tile-map j))]

(var key "")

(when (= (. (. tile-map j) i) 0)

(when (or (= 1 i) (= 1 (. (. tile-map j) (- i 1))))

(set key (.. key "l")))

(when (or (= tile-width i) (= 1 (. (. tile-map j) (+ i 1))))

(set key (.. key "r")))

(when (or (= 1 j) (= 1 (. (. tile-map (- j 1)) i)))

(set key (.. key "t")))

(when (or (= tile-height j) (= 1 (. (. tile-map (+ j 1)) i)))

(set key (.. key "b")))

(if (= key "")

(tset new-map j i 8) ;; center tile

(tset new-map j i (. bg-tiles key))))

(when (= (. (. tile-map j) i) 1)

(tset new-map j i 19)))) ;; blank tile

new-map)

For assets, I made tiles in Aseprite, which made the simple pixel art feel approachable. The trick I used to keep things manageable was to pick the Game Boy palette, which only has 3 distinct colors. This prevented decision fatigue trying to color things just right. The generated levels look pretty good, as far as I am concerned. My next steps are creating a player object and animating it with assets I have already created. I’ll report back if there are any new or interesting things I learn in the process of making the game more complete. You can see the code for the game on my GitHub repo here. Below are some screenshots of mining levels I have created.